Baseball is not a game for everyone, but I've found that those who love it will almost always have a favorite player. And their love for this player likely comes less from their skill or batting average than it does from some characteristic that they see (or would like to see) in themselves.

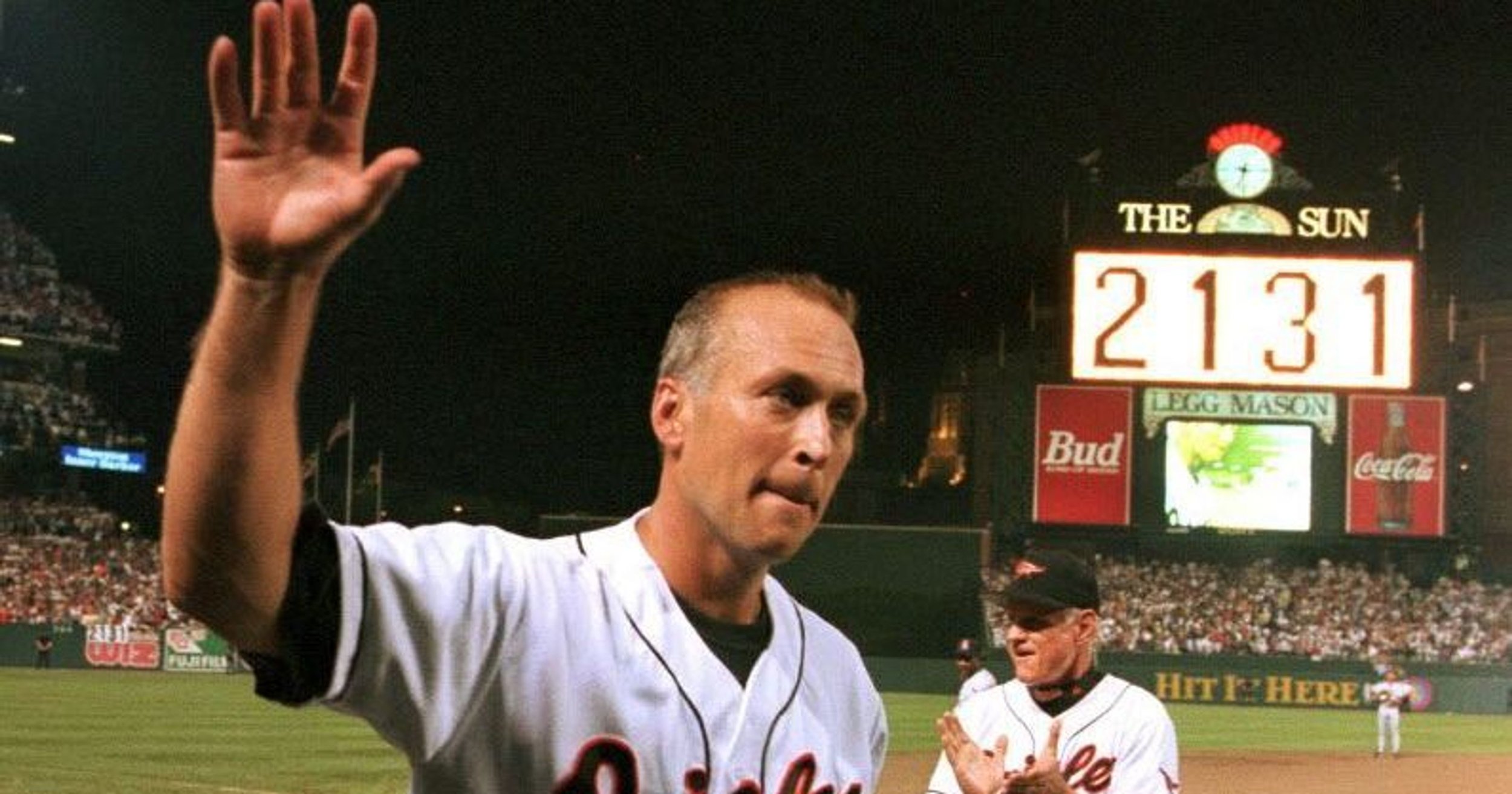

For some, it is the unbridled confidence of Ricky Henderson, for many others it is the strong will and quiet courage of Jackie Robinson. For me, that player is Cal Ripken Jr.—and not just because I'm named after him. Cal Ripken was nicknamed the Iron Man after he broke Lou Gehrig's (a.k.a. the Iron Horse) record for the most consecutive games played with a streak ending at 2,632 games. Besides Ripken's incredible career numbers, to me "the streak" was what made him my favorite. During that streak he played with various illnesses and injuries, but always showed up every day to do his job.

Photo source: USA Today

If I were asked my second favorite player however, I would not hesitate to say Greg Maddux. Greg Maddux pitched for the Cubs, Braves, Padres, and Dodgers over the course of a 23 year career and is one of the greatest pitchers of all time. He has the second most wins (355) of any pitcher in the live ball era, the 10th most strikeouts (3,371), won 4 Cy-Young Awards, and is the only pitcher to win at least 15 games for 17 straight seasons. And while, those numbers already make him undeniably great, to me his greatness comes from another, less discussed statistic. Namely, the 18 Gold Glove Awards he won which are given to the best defensive players at each position each year. This is more than any other player in history.

Photo source: National Baseball Hall of Fame

My admiration for Greg Maddux has grown long after his retirement because of a somewhat recent phenomenon known as “the yips." The yips is a real medical condition where there is a spasm in the wrist but in baseball it usually refers to the loss of ability to make short, simple throws. The first I heard of the yips was in relation to Matt Garza who is a highly skilled pitcher that struggles throwing the ball to first base.

This is a guy who could throw a well-located 85 mph slider consistently, but when asked to field a soft grounder and throw it 50 feet to first base, he often failed. John Lester suffered from a similar issue with throws to first base.

In recent years, this problem has increased with more and more pitchers, unable to make simple throws but still throwing 95 mph fastballs to a 3-inch square over and over, once they get on the mound. There are almost comical instances of pitchers under-handing the ball from across the infield for fear of throwing it into the stands or even just fielding the ball and racing the batter to first base for the out.

I can't be sure of the exact cause, but I do know that pitchers have become more and more specialized over the years. They are used in very specific situations for certain hitters. Not to mention the competition to make it to the MLB is so intense that to make it as a pitcher, you must operate under the assumption that every second spent not working on pitching would be decreasing your chances of making it in the big leagues.

But I think Greg Maddux had a different idea of what makes a great pitcher. It wasn't an overpowering fastball or a nasty curveball. It was an intelligence that exploited every possible advantage he could. There is one story told of Maddux pitching to Jeff Bagwell during the regular season and purposefully allowing him to hit a home run so that when he would face Bagwell in the playoffs a few months later, Bagwell would be looking for that pitch only to have Maddux deny him.

Photo source: National Baseball Hall of Fame

He understood that once he let go of each pitch, he was now another infielder. So he could rely on his incredible ability to locate pitches wherever he wanted and hope the other 8 guys on the field would be enough. Or he could take some extra ground balls each day and become a major league infielder as well. As a middle infielder, back when I played baseball (cue Glory Days by Bruce Springsteen), I always appreciated a pitcher who could consistently field ground balls up the middle, freeing me up to cover other areas of the infield. For very little effort, Maddux was able to make his infield that much more impenetrable. And for that extra effort, from 1990-2008 he was awarded with every NL Pitching Gold Glove, except one.

And this is why my other baseball hero is Greg Maddux. It wasn't the strikeouts, the wins, or the change up. It was that he was a true generalist. He wasn't the most overpowering pitcher with the nastiest off-speed pitches but he was good enough. Pitchers can lift weights and train to throw harder but at a certain point, being able to throw 100mph is genetic. But Greg Maddux made sure he was as good as he could be in every other aspect of the game. His defense, his movement, his location, his knowledge of the opposing team and each hitter's weaknesses. He wasn't a bad hitter either with a .171 lifetime batting average which is great for a pitcher. After all, stellar individual statistics are only meaningful insofar as they help your team win.

While Cal Ripken Jr. said "there is a job to be done, so I will do it no matter what," Greg Maddux was saying "there are several jobs to be done, and I'm not going to let any of them fall through the cracks." Both worth admiring but for different reasons.

This push for specialists goes beyond baseball though and is even more prominent in how one is told to find a career. So much time in universities these days is spent choosing what your major is, and then "what are you going to specialize in?" And then with your first internship "what do you want to focus on?" Some of this comes from an old assembly line model where you had to be superior at a very particular part of a given process so that things moved as efficiently as possible. But now, most of these processes are digital and will be taken over by computers and artificial intelligence where humans cannot even hope to compete (just consider the human brain can perform slightly less than 1000 operations per second while computer processors can perform about 10 billion in that same second).

Photo source: Mashable

So maybe more specialization isn't the answer anymore. Maybe it's the ones who can harness the thing humans still do better than computers—creativity. By combining several skill sets and learning about the other areas of the process, humans now have the ability to innovate and create while leaving the specialization to the computers. It's the software engineer who also understands marketing. Or the lawyer who is well versed in macro-economics. Never needing to be at the top of the field in any of these areas, but high enough to see the gaps and opportunities to produce amazing advancements.

Baseball has changed over the years, but the rules have hardly changed at all in the last 100 years and probably won't in the future either, so I doubt this specialization trend of "set-up men" and “the yips," is going anywhere. But I think the rules of how careers are carved out are changing rapidly. One doesn't need to be the best anymore. In fact, no human will be the best in most cases (unless they artificially increase their brain's processing power). But it is possible to be a Greg Maddux and get to a high level in several areas to see the solutions that the specialists/computers could never see. It's more work but I think it's worth it.

Sources:

https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/maddux-greg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greg_Maddux

https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/maddugr01.shtml